In my early days as a journalist, a senior editor once narrated, during a discussion we had, how elections were won and lost in some riverine areas of Nigeria’s Niger Delta where he once lived. It’s never something to hurry about, he said.

More like preparing some African delicacy, everything regarding election result computation doesn’t happen at once. Like my elder sister whom I learnt culinary skills from would put it, you add ‘this first, and then you put this’ next. One after the other. And so on and so forth.

Depending on the kind of intended dish, there’s usually time to add specific ingredient to the pot, to get the desired taste. That’s how mouthwatering meals are made. They don’t happen otherwise.

“They (politicians) wait for results in the towns to be announced first before they start bringing the results from the swampy areas. The ones from the swamps are the results that determine who wins elections,” he explained.

Given the terrain of the oil rich Niger Delta, it understandably takes longer time to navigate the swamps with bags of election results to the city centre on canoe or some other mode of transport as the case may be. So, the delay, to some observers, is understandable.

What is implied from the editor’s story, however, is what happens in between the tabulation centre to the announcement centre known only to the electoral participants or their collaborators.

Though a story about the Niger Delta, it might well stand for the Nigerian political class anywhere in the country. It’s the reason a candidate far behind in ballot figures, for example, could suddenly be running neck to neck or assume a lead that, for want of a better word, leave his opponents wondering.

I couldn’t help recall, in their starkest form, the editor’s words as I waited for the announcement of the results of Nigeria’s presidential election which held on February 25. It was an endless, insufferable wait.

After three days of waiting, Bola Tinubu of the ruling All Progressives Congress, was declared the winner. He defeated Atiku Abubakar of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), and Peter Obi of Labour Party (LP) in a contest that featured eighteen candidates.

Tinubu’s announcement as winner didn’t go down well with the LP and PDP as prior to the declaration, they had raised objections and called for the cancelation of the election on the ground that the process leading to the collation of results was compromised.

At the time the editor spoke about late arrival of results from riverine areas proving to be spoilers, announcement of electoral results in Nigeria weren’t done real time. They were collated from various polling units to where the results were officially announced.

Before the February 25 elections kicked off, Nigeria’s electoral umpire, the Independent National Electoral Commission, (INEC) led by Professor Mahmood Yakubu, had informed the world that with the use of Bio-Modal Voter Accreditation System (BIVAS), results of elections would be recorded and transmitted electronically for all to see. It’s part of the fruits of the Electoral Act that was signed into law by outgoing President Muhammadu Buhari, we were told. With the BIVAS technology, INEC officials and some other experts argued to no end that the rigging that characterized past elections in Africa’s most populous country, would no longer have effect. Not true, say PDP and LP.

Their argument is based on the fact that on the day of the presidential and house of assemblies’ elections, the upload that people expected to see, didn’t happen.

What were seen, instead, were INEC officials announcing results in the various centres where elections held. These are seen from videos of the polls recorded by people who witnessed them.

More than 24 hours after scheduled elections were supposed to have been concluded, the results of the presidential election were nowhere to be seen on INEC’s website.

There are many who blame what happened on an unholy alliance between corrupt INEC officials and politicians desperate to ensure they remain in power but Festus Okoye, INEC’s Chairman of Information and Voter Education Committee, thinks otherwise. The delay in uploading the results of the elections, he said, was “totally due to technical hitches.”

According to BusinessDay newspaper, “The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) proposed N305 billion for the conduct of the 2023 general election last May, a 62 percent increase over what was spent on the 2019 general elections.” Yakubu has been in charge of INEC since 2015. Notwithstanding these, “the familiar frustration of Nigeria’s old logistical nightmare” continued. Despite loud assurances, the paper added, “the electoral umpire didn’t live up to the billing.”

Because the results of the presidential election were not uploaded electronically, they, like in the swamp scenario, arrived in ‘trickles’ to the collation center in Abuja, and what happens in between when the elections ended in the polling units and voters dispersed, to when INEC declared the results to the world is left to the imagination. If past experience is anything to go by, it’s easy to deduce that a lot of “water passed under the bridge” as we say it in Nigeria.

The BIVAS issue aside, millions of Nigerians, in different parts of the country, waited hours on end for the poll to kick off. Both the old and young, who left their homes early for the polling centres to vote, could not do so because INEC officials either arrived late to the polling centres, or were nowhere to be found. In some cases, some ballot materials were found to be missing, thereby putting the election on hold and further prolonging the agony of Nigerians. Some voters also found to their shock that the logo of the Labour party was missing in ballot papers.

In many instances, elections kicked off long after they were supposed to have ended. As a result, voting extended long into the night in many states across the federation. What a sight it was seeing people at polling centers with torches and vehicles light illuminating polling units to enable the process be completed. This was so, as many intending voters refused to leave the polling units until they had cast their vote.

More than at any time in Nigeria’s history, it could be said, people insisted on voting in this year’s election. Many did so, believing that their votes would count. Apart from the frustration caused by INEC, many voters were harassed and assaulted by political thugs who invaded polling centres in their numbers to threaten people and cause mayhem. Besides disrupting voting, some polling booths were destroyed or set ablaze. To this moment, there has been no known arrest of hoodlums or thugs who are either known or identifiable from the videos circulating online.

We saw, from the clips, instances of policemen in Lagos looking the other way or choosing not to act as thugs threatened voters or asked them to vote for the APC. There were also reports of incidence of underage voting in some parts of the country. In all of these, allegations are rife that some INEC staff colluded with members of political parties to alter figures in their favour.

This background set the stage for the protest that trailed the announcement of the APC as winner.

It’s not just LP and PDP members that are protesting. Millions of Nigerians, depending on where they stand, are flummoxed. Once again, the giant of Africa, as passionate Nigerians love to describe their country, failed to live up to the demands of a free and fair election.

In the emergent chaos that trailed the elections, politicians assumedly generally had a field day. And the harvest was plentiful.

As I remarked in a response to a colleague’s comment about the Nigerian election in a WhatsApp group we both belong to, “every new election in Nigeria is the worst. It’s the mark of progress.” It’s a statement or variation of what I have heard many Nigerians utter since 1999 that the return to civilian rule, after decades of military rule, kicked off.

But there was something good about the February 25 election. It was a keenly contested poll involving three major political parties–no more two,(APC and PDP) deemed “miserable choices” that Nigerians were saddled with.

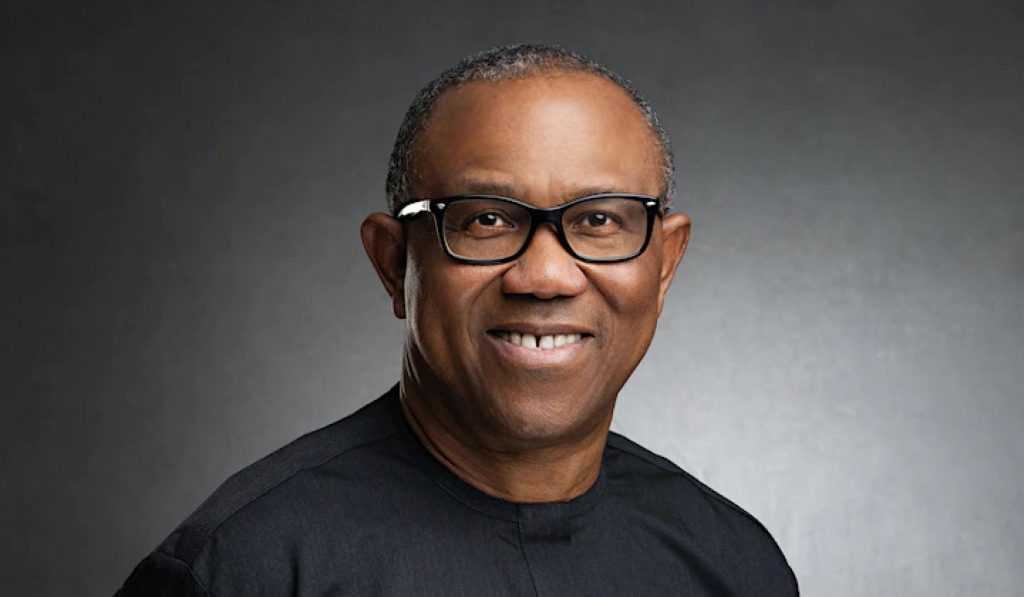

Peter Obi, the LP candidate, who was tipped by some opinion polls to win the election, placed third with over 6 million votes, second to PDP with nearly 7 million votes while the APC amassed over eight million votes. Despite not winning the election, Obi, who enjoys massive support from many young Nigerians, won all but four of the states that he was projected to win: Benue, Rivers, Akwa Ibom and Bayelsa – the last three of which are in the Niger Delta. According to Channels TV, in the case of Rivers, Obi polled 62,450 votes in Port Harcourt Local Government Area, followed by the PDP with 7,203 and APC with 5,562.

In Makurdi, Benue, Daily Post reported that LP won with 48,228, followed by APC with 15,900 and PDP 5134.

In Uyo Local Government Area, other media show Obi secured 27,534 votes followed by PDP’s 12,245 and APC’s 7,769.

In Yenegoa Local Government, Obi got 22,261 compared to PDP’s 14,308 and APC’s 6,651.

Port Harcourt, Makurdi, Uyo and Yenegoa are all capital cities or major towns. Despite these convincing victories, when results began arriving from the hinterlands and total results were announced, the effect was clear. Talk of masterstroke and you will be dead right.

In the poll projection for Obi, some analysts’ calculation was that, in the event of LP not able to secure an outright win, with PDP and APC slugging it out in their traditional northern stronghold, the outcome could force a run off, with the LP being one of two parties to contest for it. But the PDP trailed APC in the battle that it insists, was rigged.

However, Obi achieved the biggest victory in modern Nigeria’s electoral history by defeating Tinubu in Lagos, a state where the latter was a two-term governor.

Lagos, by composition, is a mini Nigeria as it is a melting pot of the country’s diverse ethnic groups.

Obi also won in the Federal Capital Territory, with Abuja as the country’s seat of power.

To that extent, it can be argued that many Nigerians clearly desire change from their current abject situation. Years of misrule and monumental corruption had combined to ruin the future of generations of Nigerians and life simply cannot continue that way.

With the PDP and LP insisting on contesting the result of the election, the court may, in the final analysis, have the last say on the matter.

What a shame!

Anthony Akaeze is an award-winning journalist and author of four books and co-author of the recent book published by Taylor and Francis in the UK titled Media Ownership in Africa in the Digital Age: Challenges, Continuity and Change.