Football fans watch the UEFA Champions League Final in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

On June 3, 2017, people gathered in their homes in Kolwezi, a mining town in the southeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). They began to watch the European Champions League final match when, suddenly, the power went out. Young and old football fans angrily left their homes for public bars in areas where power is more stable. They clustered around television sets and overflowed into the street.

“I came here to watch my favourite player, Cristiano Ronaldo, because I have no power at home,” said local resident Clement Kasil.

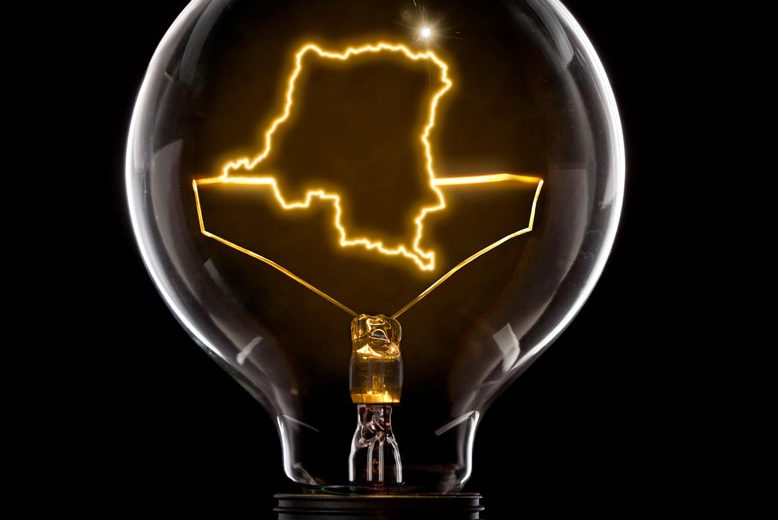

This power outage is part of a much bigger problem in the DRC which has one of the lowest electricity supply rates in the world. Only about 13.5 per cent of the population has access to electricity. The lack of power contrasts markedly with the abundance of mineral resources below ground.

“With 80 million hectares of arable land and over 1,100 minerals and precious metals identified, the DRC has the potential to become one of the richest economies on the African continent and a driver of African growth, provided the country manages to overcome political instability,” the World Bank says.

In this paradox, the mining industry offers a possible solution to the country’s energy crisis. Projects need power to operate, so what if, instead of generating their own electricity on-site, mines could become reliable and essential customers, guaranteeing business for utilities and independent power producers alike?

In favour of private investment

In the DRC, the mining sector and power sector have been linked for years.

“The existing electrical installations in the DRC, until independence in the early 1960s, were implemented by mining companies and processing companies,” explains Nestor Mwemena Kamwabe, the former CEO of the national energy company known as SNEL. This was largely steered by the big state-owned mining companies, Mwemena says.

The focus on mining development meant that private power plants were designed according to the needs of the mines. To exploit the DRC’s major mines, the colonial government built hydroelectric power stations close to mining deposits — the DRC has major hydroelectric potential, explains Mwemena. But over the years a lack of maintenance caused by perpetual wars and economic and political instability meant the infrastructure was not maintained.

In 2002, the government released a new mining code meant to liberalize the mining sector and attract private investment. The DRC’s government resolved to gradually withdraw from the electricity sector. The idea was to make the sector more competitive while creating an institutional, legal and regulatory framework for attracting public and private capital.

Major companies, largely based in the mineral rich southeastern portion of the country — formerly known as the Katanga province — gradually moved in. To continue working, they had to install generators or purchase electricity from neighbouring Zambia. A few large private mining companies, most of them located in remote areas, invested millions in the rehabilitation and modernization of existing government infrastructure.

“For the case of Katanga province, mining companies are, of course, significant potential investors in the DRC electricity sector, as they consume more than 70 per cent of the energy currently produced,” Mwemena says. “The excess energy it can produce can significantly serve local communities.”

It’s a model that is supported by the World Bank. In a 2015 report, The Power of the Mine: A Transformative Opportunity for Sub-Saharan Africa, the bank acknowledges the importance of energy for eradicating extreme poverty and calls on the mining industry to work more closely with electricity companies in the region.

“Power–mining integration can create a win-win situation,” the report says. “Mining companies could be anchor customers for utilities, facilitating generation and transmission investments by producing the economies of scale needed for large infrastructure projects, in turn benefiting all consumers.” Basically, because they need so much energy to extract resources, companies are forced to figure out how to generate power which can speed up energy access for communities.

Does the power trickle down?

About 100 kilometres away from Kolwezi, electricity is equally scarce in the town of Fungurume, home to 235,000 inhabitants.

Samuel Kabulo, an apostle of the Restoration in Jesus Christ Church, says he has been having trouble since he was posted to Fungurume. Kabulo heads a new denominational radio station called “The Radio of Restoration in Jesus.” Getting his message out comes at a high cost — the pastor must generate his own electricity.

“When there are power cuts like this, we are forced to spend money from our pockets to buy five litres of fuel per day that costs five dollars [US],” Kabulo complained.

The Tenke Fungurume copper mine in the Katanga province of the DRC.

Lundin Mining

The lack of power for residents of Fungurume is contrasted by the massive production happening locally at Tenke Fungurume Mining Company, a controversial Chinese company. The multi-billion dollar company owns one of the world’s largest known copper and cobalt reserves. Their production accounts for 3 to 4 per cent of the DRC’s total GDP and requires a massive amount of electricity.

So, in 2009, Tenke Fungurume Mining Company invested more than $215 million US to modernize a nearby hydroelectric power station. The Nseke power station, built in 1956, was once the largest power-generating plant in the southern Katanga mining region. It had fallen into disrepair and the mining company, needing power to continue to extract resources, wanted to fix it.

Since 2009, three out of four hydro-generators have been rebuilt, producing 65 megawatts each. Though it could be enough energy to provide power for hundreds of thousands of homes, the energy is mostly being used to power the mining operations. According to Alexis Seya, Tenke Fungurume Mining’s power administration engineer, the total rehabilitation of the fourth generator group is planned for 2018. But when it’s finished, it will not guarantee the total electrification of the nearby cities, Fugurume and Tenke.

“The rehabilitation of the Nseke Dam is 95 per cent executed,” he says. “Once the fourth group is finished, it will be in reserve due to the storage capacity of the water, which only allows us to operate with three machines. If we operate all four machines, the lake will empty to a level below the minimum operating level, which means that the population will not totally benefit from the electricity generated by the Nseke dam,” says Seya.

This is despite the fact that power was promised to the community and electrification is a priority for Fungurume, which depends mainly on the mining company for employment. The few in Fungurume who are currently connected to the grid need about 3 megawatts of power and the company provides half that to SNEL, but isn’t able to do so consistently, explains Seya.

“Today we feed a part, tomorrow we feed another part,” says Seya. Although the high-voltage power lines cross the district of Fungurume from one side to the other, the infrastructure is not in place for people to connect to the grid, so most inhabitants in this area continue to struggle to have reliable energy.

The double bind

In 2011, another of the country’s largest mining companies, Kamoto Copper Company (KCC), decided to partner with the state-owned SNEL to revitalize a high voltage electrical system project. KCC invested over $368 million US in repairing the Nzilo hydroelectric power station and upgrading a transmission line carrying electricity some 1,700 km from the Inga hydroelectric plant on the Congo River to Kolwezi in the Katanga mining region.

“Repair and refurbishment of the power distribution and transmission facilities from the Inga dam to Kolwezi’s main distribution hubs are nearing completion,” says Gustave Nzeng, chairman of the board of the Kamoto Copper Company. “This has had a major impact on the reliability and stability of the supply of power to the Kolwezi region.”

Yet again, despite this investment, life has yet to change meaningfully in the region, much of which still labours in the dark. But, says the Kamoto chairman, after work is completed on the Nzilo dam, 10 per cent of the electricity generated — over 40 megawatts — will go to the local people.

“The public/private partnership agreement between SNEL and Kamoto aims to deliver 450 megawatts of reliable and stable power to SNEL’s main distribution hub in Kolwezi,” he says. “The project will redeploy excess capacity on SNEL’s grid, which will be available for consumption by the local communities.”

And while the power itself may be available, the infrastructure required to convert high voltage industrial power to lower voltage electricity for domestic use comes at an enormous cost. Fridolin Kumbu, the provincial director of SNEL, questions whether the energy generated by mining companies will make it to the community.

“Will this power actually be delivered to the population while some other mining and industrial companies still need more energy? Will the population be sacrificed to the profits of other companies, which are major consumers of electricity and large customers of the national electricity company?”

Without access to reliable power, residents in Fungurume, some residents have decided to use small solar panels to generate electricity.

For Kumbu, this scenario puts the government in a double bind. “We must be able to satisfy the energy needs of companies, without which the same populations who criticize us could end up unemployed and would not even be able to afford electricity bills. We will try to satisfy the population and the mining companies,” says Kumbu.

For observers like Kumbu, plugging industrial power into the local grid is still the way of the future.

“The use of foreign investors is still the fastest solution”, says Kumbu.

Risks of privately funded power

In the past, the government has said that “electricity must cease to be considered as a luxury or the preserve of only urban and industrial centres. All Congolese, wherever they are, must have reliable electricity.” But relying on private companies to power the country is complicated.

“There are risks of this integration in the sense that the financing of the electricity sector is large and the reimbursement can be hypothetical with the fluctuations of the prices of metals on world market,” says Willy Kitobo Samson, Haut-Katanga province minister of mining, environment and sustainable development. Companies are focused on profits and impacted by changes in the market, meaning that if market prices fall, community electrification may suffer.

A report from the Columbia Center for Sustainable Investment puts it another way: “For a mining company, the goal is to maximize cost-savings. For a host country, the challenge is to maximize welfare gains by leveraging any investment in power infrastructure development for the electrification needs of the country.”

Serge Tshibangu, a resident of Kolwezi, tells me companies aren’t building hydro projects out of the goodness of their hearts, so he wants to see the government be transparent. “To me, the state must change and be more transparent and more responsible. It is up to the state to address the power challenges with mining royalties,” says Tshibangu.

There is one potential spoiler in all of these plans: the drastic change in climate poses a serious challenge.

“We have a problem with hydrology, which means that we cannot get enough water in our watersheds to allow us to exploit our machines to the full,” says provincial director of SNEL, Fridolin Kumbu. “Our raw material is water to turn our turbines, but unfortunately we are also suffering the harmful effects of climate change.”

To try to offset this situation, SNEL has signed partnerships with private companies to install solar and thermal power stations in the new provinces of Haut-Katanga and Lualaba. These projects are gradually being put in place, and are expected to be less impacted by climate change.

In Manono, a remote part of Haut-Katanga province located south of the DRC, a 1 megawatt solar plant (two hectares of panels) is under construction. Built by Congo Energy, it will supply disadvantaged neighbourhoods with electricity and will be integrated into a SNEL distribution network. In the case of Kolwezi, the local government has partnered with a solar distribution company to power a health centre, among other projects.

Kumbu insists that a lot is being done to bring energy to communities but to make projects happen they need private investment. “All of this requires heavy investment, that is why the government has liberalized the energy sector. We no longer have the monopoly, investors are welcome.”

This content was produced with the support of the Access to Energy Journalism Fellowship and Discourse Media. The piece was edited by Lindsay Sample and Richard Poplak, with fact-checking and copy editing by Jonathan von Ofenheim. The graphics were created by Caitlin Havlak. Discourse Media’s executive editor is Rachel Nixon.[:]